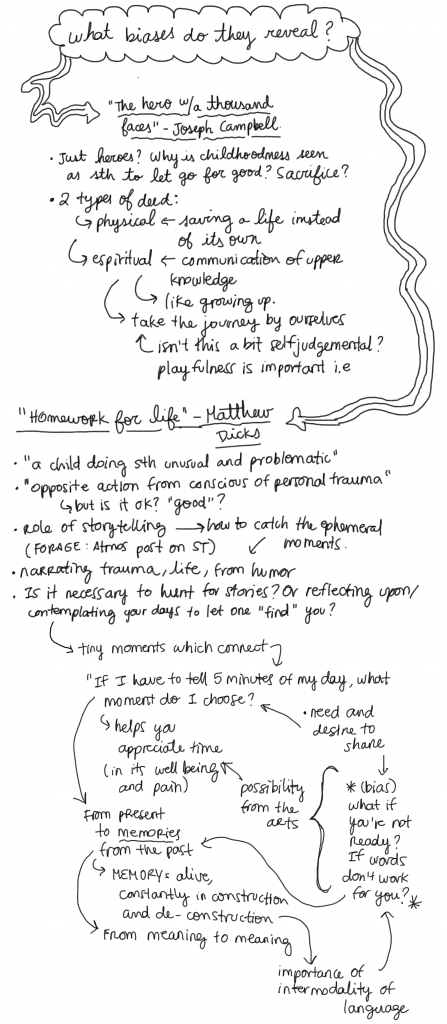

We have been foraging through sources on storytelling. This week, we engaged with the works of Joseph Campbell and Matthew Dicks, tasked with identifying biases in their approaches to this complex, yet wonderful, narrative art. By dialoguing with their ideas and reflecting on how shared experience enacts a performative sense of belonging, I began to navigate a series of questions.

Campbell’s model of the “hero” who conquers “underdeveloped” parts of the self reveals a moral discourse that strikes me as potentially pretentious or idealistic. Why must we sacrifice an elemental part of ourselves (a part deemed “wrong” or “immature” by a moral standard) for some abstract “greater good”? If experience-based learning is foundational, then our earliest identity-shaping experiences are crucial to understanding how we became who we are. Therefore, the complete denial or suppression of these parts through a heroic-ritualistic process can be dangerous, problematic, and ultimately hurtful. Perhaps it is more about relocating that archetype or dialoguing with it. This draws my attention to the inherent bias within the very concept of “sacrifice.”

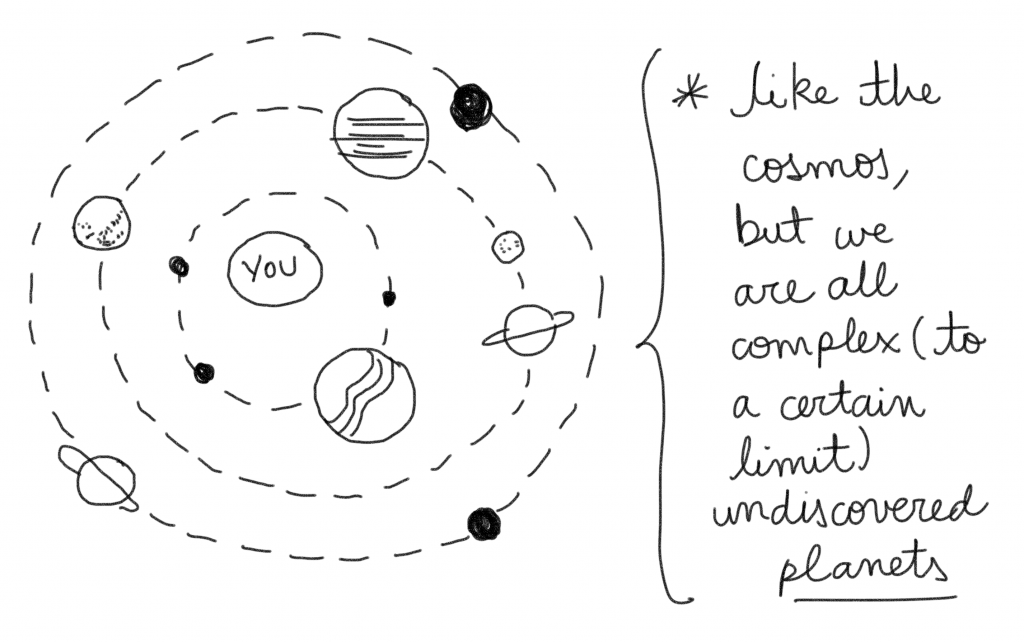

This is not to promote individualism or a narcissistic viewpoint, but to argue for seeing the self as an interdependent core, around which others orbit and are orbited in turn. Furthermore, if mythology is built upon archetypal narratives, what becomes of the vast diversity of other archetypes?

Shifting to Dicks’s suggestions for capturing fleeting daily moments, I find he largely overlooks contexts of high stress. His proposal, sadly, lacks any mention of this. He does not consider how to adapt the assignment for cultural contexts where priorities are different, and the rhythm of life is so intense that there is no time to write, for example, five pages about one’s day.

What if, instead of or alongside “compromise” and “faith,” we were to focus on hope? How can we practice hope, not as an abstract concept, but as an identitary practice that sharpens our perception of these moments? How can we apply this “homework for life” when the day feels endless? Is the goal merely to feel “better,” or is it to notice something fundamentally different?”

Leave a Reply