Just came across some questions on my personal agenda: What structures support my authenticity? What boundaries allow me to be? Can I include authenticity in my sense of belonging? Can I feel that I am a variation within my system of references? In what ways do I feel transgressive or different?

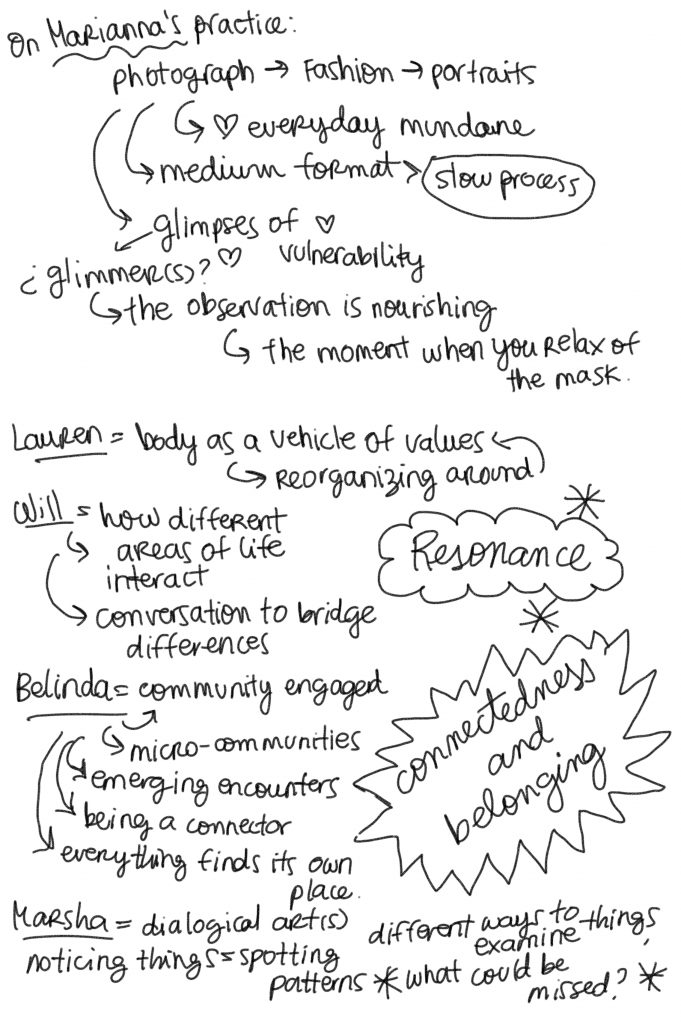

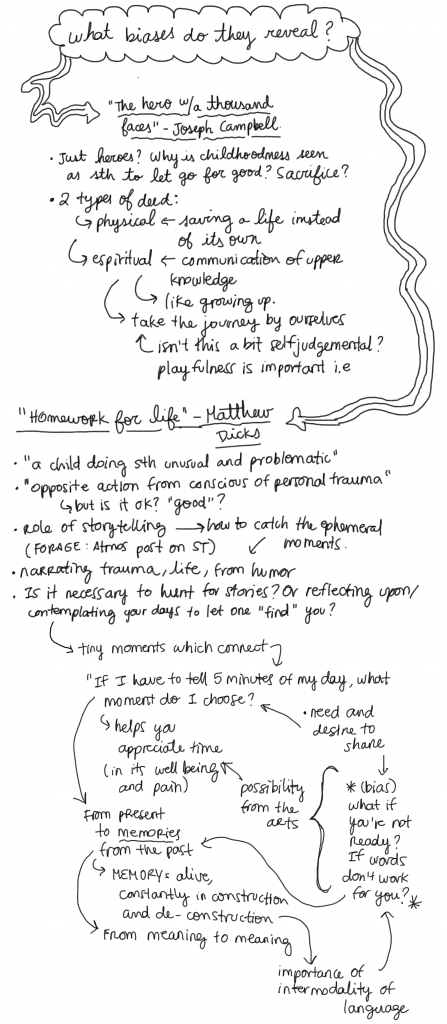

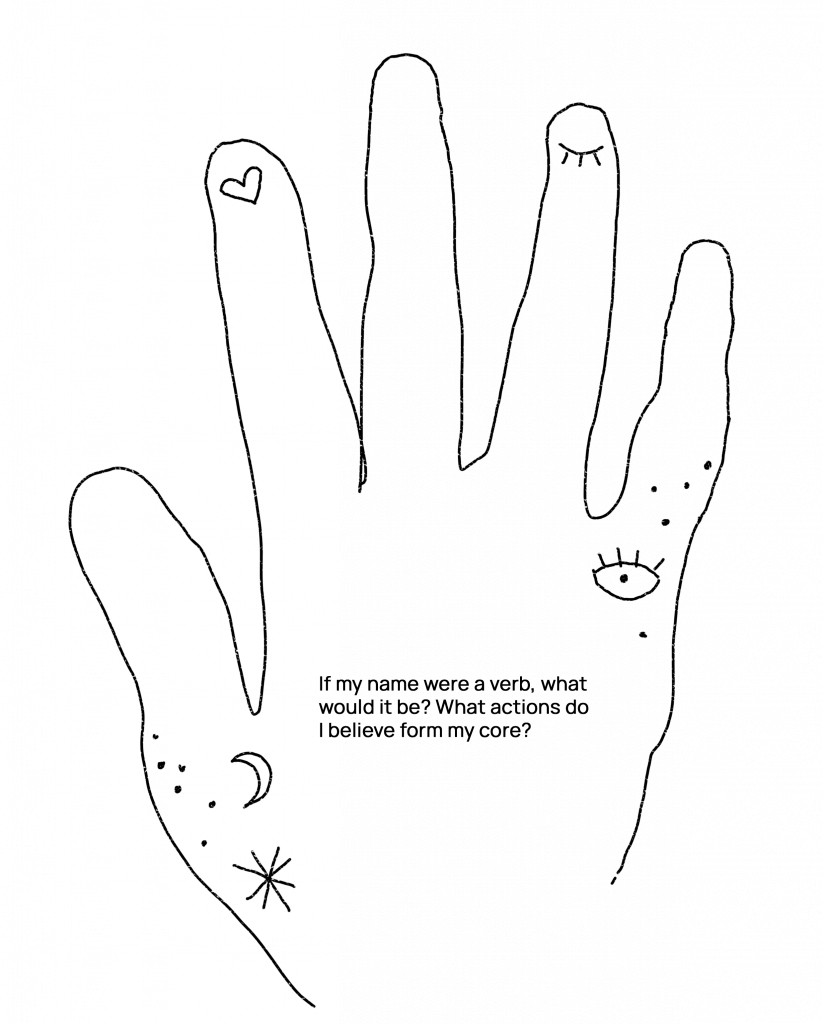

What does it mean to be authentic in practice? I don’t know if I arrive with answers or truths, but this question makes me think about my way of creating and working. About how everything I do involves a complex, yet rewarding, opening of the heart. That is, I manage to stop residing in my head in order to give myself a space to feel with my hands: folding paper, writing, moving images on a computer to connect with what I’m trying to express from the suggestive silence of those narratives that are not oral or written. And that’s how I return to the meeting point with one of my cohort’s friend, who was just sharing his notes with me regarding the act of writing and the possibilities of translation that it entails. What do we translate when we write? What is trans-localized? As he mentions, I share his view that it is the affects that are relocated. That’s where the magic of the narrative act lies for me: the power to give a second chance to an other that resides within us.

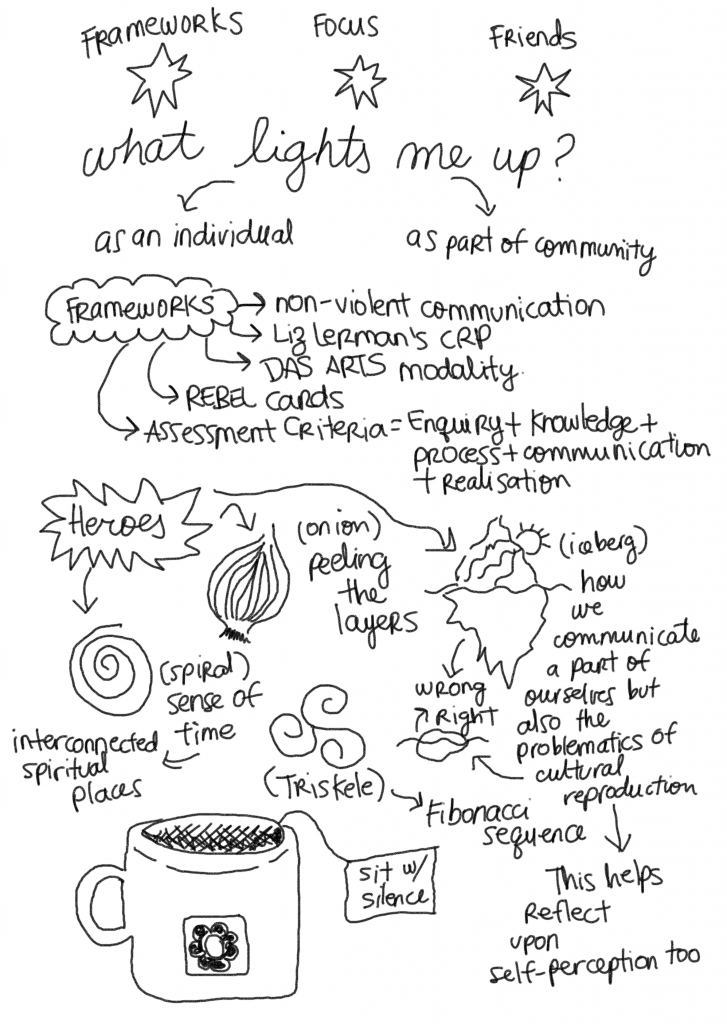

So, this leads me back to think about one of the questions on my agenda: what structures support my authenticity? Generally, they are rigid categories we are born into. Methods of survival to not rock the boat too much in a context in crisis, where we try to be functional in the best way possible, aware that along the way not everyone will be performing in the same way, or with the same act of care. Nevertheless, we don’t stop trying. But at some point those categories break because they wound us, they judge us. That’s how I ask myself, if boundaries are healthy, how have I been learning them? They were taught to me as walls, but perhaps they are like mountains that can be crossed to reach new explored territories.

The mountains allow me to be. Throughout my practice they have made themselves present to remind me that my pace is not a problem, because like the haiku that speaks of the little snail crossing Mount Fuji, I too reach another horizon. That’s how my practice keeps transforming: it is restless, it is curious. It is not satisfied with something “well done”, but with something that can generate an echo of continuous molding, especially if it can be shared with others. The mountains are the geographic and affective space where I can reflect on what is working well and what could work better. This is where it sometimes gives way to a demanding character. The temperament of someone who believes they must suffer to achieve, for whom nothing is ever quite enough, and I consider this partly my cultural inheritance, a continuous dialogue, perhaps even in its most unforgiving aspects.

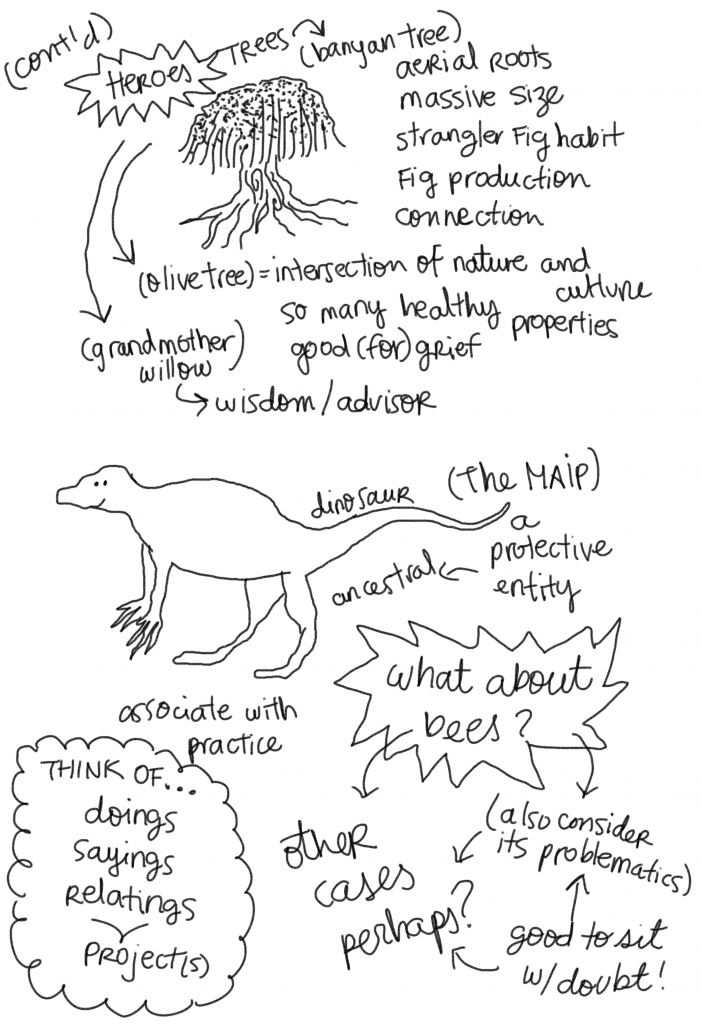

I was born in a context with possibilities and privileges, but affirming that does not imply denying everything that comes with growing up as a woman with migrant parents in a chaotic city: as wonderful as it is violent. In that sense, my first roots are situated in the fear of burdening others, of being a problem, of being weird and having no restraint. However, years later to the present day, I find myself somewhat different. I no longer stop doing things out of fear, rather I keep doing them because I love them very much. So, when I think about the question from my agenda: What boundaries allow me to be?, I address it with another question: “Where else could I find other roots?”. That’s how the transformation of my practice begins. Finding common nodes with strangers: those we meet in the space of a consultation, workshop, class, or creative accompaniment, a space where our completely foreign and differentiated contexts can coexist with kindness and weave a common language: the visual and editorial arts.

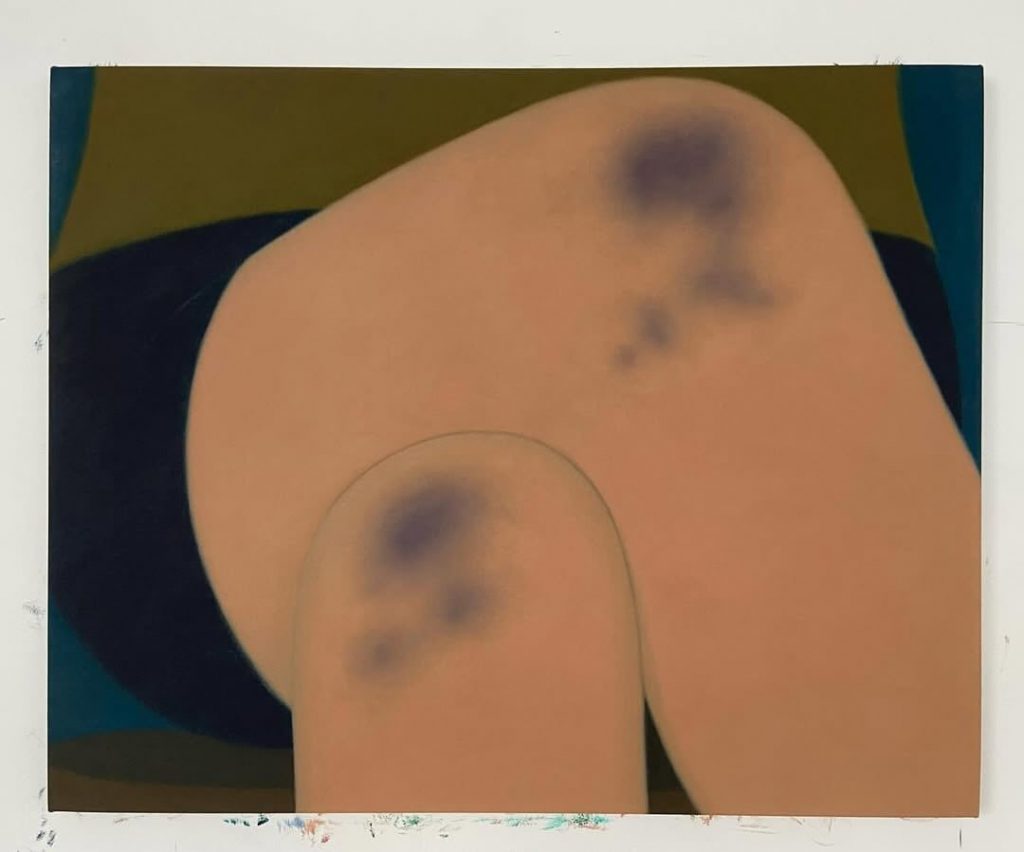

And it’s that I feel that when we are in front of a stranger, we become uncomfortable, because we find ourselves face to face speaking “the same language”: in this case, Peruvian. But, what happens when we enter an imaginal space where languages have no geographic or linguistic categories? What happens when what we share comes from a color, a scent, a sound, or a texture? Curiosity and doubt emerge. The desire to understand appears, and also the frustration of not feeling the same. But the arts are adaptive in essence, so we turn to another one to navigate the discomfort with intuition, and with that, perhaps turn the communicative restriction into an expressive possibility. In this way, it is possible to create meeting bridges, where we are seen in our most uncomfortable parts, those that sometimes rest in secret.

This is something that also sometimes comes to my mind: sometimes, when I am in front of someone I don’t know, I feel freer to share something that is very personal and uncomfortable to me, but that, of course, is also ready to come out. However, sometimes I find it more challenging to reopen something personal with someone I’ve known for years. Maybe it’s just me, or maybe someone else shares this same “mischief”, but it leads me to think about how there is a powerful and beautiful possibility to create safe and deep spaces to speak about the unspeakable among strangers, as long as we can have an anchor nearby, like when they teach you to swim and show you the gutter you can hold onto so you don’t feel like you’re drowning, while you start taking your first swims.

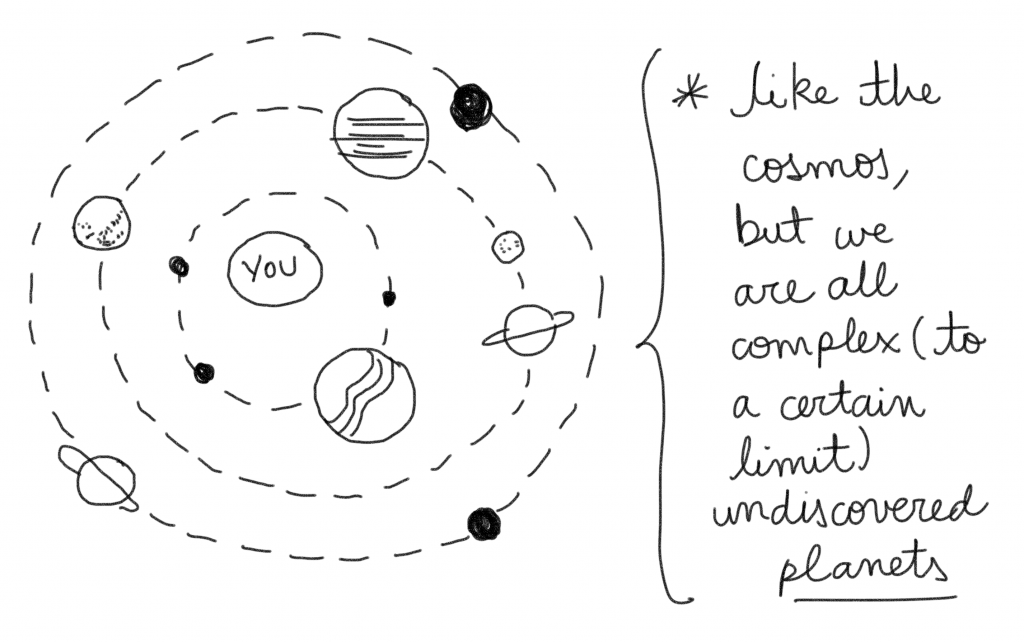

So, what is my authenticity? Is it a “what” or a “how”? I believe it is like the trunk of my tree that comes from multiple roots but branches out into many, many branches. Like the book that is inhabited by multiple narrative resources to be able to unfold diverse stories. That’s how I feel, live, and seek to create books: as bridges between the different, within me and between us as communities. That is why I see editorial practices as states of belonging. Like time-spaces for witnessing doubts and experiences that can be held as learnings (or their pivotal points). In this way, I don’t relate creativity to talent, because it has to do with a quality inherent to human beings, rooted in their openness and ability to respond to diverse environments or contexts of crisis. This connects me to the question of if I can feel that I am a variation within my system of references? I confess it’s something I’m not sure about and I don’t know if I ever will be 100% sure (something to perhaps keep revisiting later), but I do have to recognize that I am in a continuous process to better understand and propose editorial practices as another type of affective environment, because I think that books (such as manuscripts, quipus, engraved stones or wooden tablets, canvases, logbooks, notebooks, and diaries) have historically been and continue to be an important repository of personal gestures imprinted in that creative response, previously mentioned. That’s the meaning of artistry for me. And that’s the mindset surrounding the arts that I’d like to rehabilitate in the world, as many others are already doing it. After all, building communities with artistry is doing so by bodily interconnecting with others by a purpose, a question, a search, an initial curiosity that will or might navigate through similarities, conflict, change, yet hopefully keeping the same horizons.

So, in what ways do I feel transgressive or different? Like an image I saw once: remaining kind and tender in a world that is often cruel. Trusting. Trying. Hoping. I guess constantly taking care of the child in me that allows me to turn a limit into a guideline, rather than a wall, one that leans me towards curiosity by questioning the shape of things and how chaos can be a fun, emotional and authentic way of seeing them from another point of view: the one of a “stranger”. And books are the threads that aid not losing that image: new, different, complex, yet beautiful because it’s necessary, kind, compassionate and freeing. So an image, created and cared, to be witnessed along others.